Zimbabwe was one of those critical junctures in our lives. We had just fled our precarious life in Southern Angola as the civil war restarted. Zimbabwe represented a safe haven, good health care for our daughter, work opportunities for Claire, career advancements for myself and wonderful travel opportunities. As was so often the case with our overseas work, things did not work out entirely as hoped.

Zimbabwe, formerly the white run, ex-British colony and the never formally recognized, Republic of Rhodesia obtained independence in 1979 after a protracted ‘bush war’ led by various black liberation movements. By the time we arrived, the country was, more or less, stable and peaceful but under the increasingly authoritarian rule of Robert Mugabe, the president since independence. He was in power until 2017, a 38 year reign! A perfect example of ‘power tends to corrupt: absolute power corrupts absolutely’.

The former Rhodesian economy was relatively balanced, with a strong manufacturing sector, iron and steel industries, a modern mining sector and was still, more or less, in place when we arrived. It was however, just hanging in there. Mugabe’s land reforms in particular resulted in rapid decline of agricultural production and exacerbated the ever increasing ‘white flight’. By the time of his ouster in 2017 Mugabe had become a repressive dictator responsible for serious economic mismanagement, widespread corruption, human rights abuses even genocide….but I’m getting ahead of myself. While we were there he still had the unquestioned loyalty of the Shona people (the dominant tribe of Zimbabwe) and more broadly, amongst the surrounding countries, lingering respect as an elder stateman of the African liberation struggle.

We flew directly from Angola to lovely Harare, the capital city. Renown for its pleasant climate, lovely suburban neighbourhoods and a modern downtown, Harare was another world compared to our previous posts. We soon found a spacious and by our standards, palatial home to rent (the white owners had recently fled the country). It was a 3000 + sq. ft. bungalow on a large, fully landscaped property with beautiful jacaranda trees and a giant, prolific, avocado tree. It had the ‘mandatory’ perimeter security wall, an in-ground pool, large gazebo for outdoor entertaining, play area for kids and the usual, humble, domestic’s quarters out back. We also took on the existing complement of domestic staff including Kenneth, our full time gardener (& his family) plus Dorcas, the cook/house keeper.

A portion of the backyard of our ‘palatial’ home in Milton Park, a neighborhood of Harare (formerly, almost exclusively the preserve of whites). Jacaranda trees in the background, gazebo under the avocado tree on the right, kid’s playground and even a little out building used as a sewing (hobby) room.

Our pool and just a small portion of the garden. Thank God we had a gardener!

I think it fair to say that the ‘Rhodies’ (white citizens of Rhodesia) often held racist views and treatment of their domestic workers was, from our perspective, poor even abusive. We tried to establish a new rapport and working relationship but unsuccessfully. Dorcas was quite manipulative and pampered me, the perceived boss, but tried to dominate Claire, never a good idea! Exactly what her motivation was is hard to say. There is so much we didn’t know about their lives. The stark, black-white divide that existed in the country (promoted by Mugabe!) and other socio-cultural determinants made bridging that divide difficult. Whatever the case may be, things soon degenerated further. Kenneth began manifesting a mysterious illness. One day, his wife asked Claire to drive them to a traditional healer (n’anga) out in the country. Once arrived, the two of them helped Kenneth into the n’anga’s hut who without any warning, suddenly spat on him (to drive out evil spirits?). Claire, not feeling entirely comfortable with the ‘health care’ being provided, soon left. Despite the intervention of the n’anga, it was apparent that his health continued to deteriorate. A few days later, Kenneth’s wife in a panic asked again for our help. He was in full seizure and stiff as a board. I somehow squeezed him into the backseat of our small sedan and took off for the nearest state-run hospital. It turns out he was suffering tertiary stage syphilis. He never returned home. We were told his family had taken him back to the Communal Lands, where soon after we were informed he had, mysteriously, drowned. Drama of various sorts (eg. Dorcas was stealing from us, among other things) with our workers and their extended family continued until we finally asked them all to leave . A complicated and difficult process. I can’t remember how we found their replacements, William and Eva, but they were to become an important part of our lives.

William (back row, right), Eva (front center) with her son Joseph on her lap with their new baby, Sudden (named in recognition of his rapid delivery) in granny’s lap. We had an interesting visit (above) to William’s father’s home in the Communal Lands. These rural areas designated for the black population and based on tribal affiliation where subsistence farming was the primary activity, were often very poor and densely populated. They lacked infrastructure, employment opportunities and the land was often overgrazed. Nevertheless, we were very warmly welcomed and soon began our introduction to rural, tribal culture. When we first arrived and were invited into the main cooking hut, Claire, Nina and Nathalie, our visiting niece from Quebec, sat beside me on the raised platform reserved for the men. Oops…. all the women folk sat on the floor on the other side of the central hearth. The open, wood fire was where they did all their cooking. The smoke from the fire and lack of chimney would soon drive us out of the hut (conjunctivitis is a common ailment) but before leaving we noted their old-fashioned, clothes iron heated with embers from the fire and then watched in amazement as William took a hot coal out of the fire with his bare fingers to light a cigarette. That night, they killed a chicken for a special dinner with their guests.

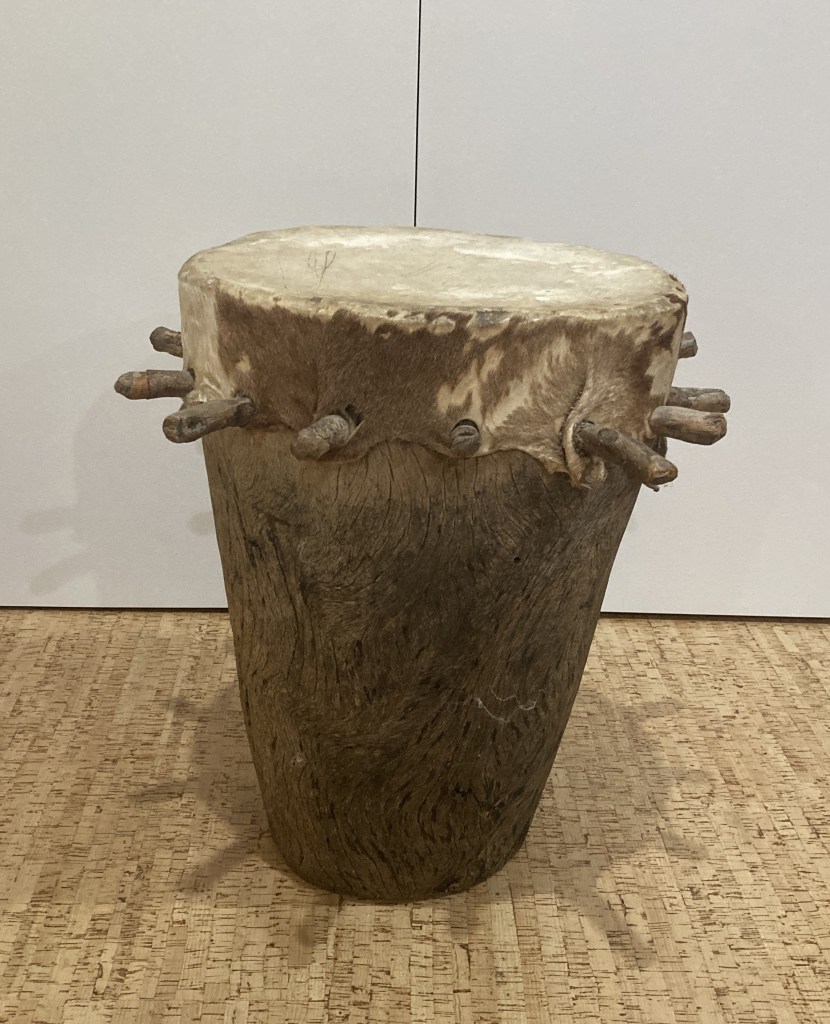

The following morning, Nina and Joseph went with the older girls to collect water at the village hand pump. It was fun to watch as they imitated the others by trying, unsuccessfully, to balance small buckets on their heads. The family compound consisted of various thatch roofed huts, all with a different use. I understand that Zimbabwe, at that time, had one of the highest rates of death by lightning in the world. Apparently, their conical, thatch-roofed huts, combined with certain geological/electrical properties of their siting act as conduit for lightening strikes with the often corresponding lethal results for the occupants. Locals believe that any such ‘act of nature’ is actually a result of a curse evoked by a malevolent n’anga, on behalf of a mean spirited neighbor or other ‘enemy’ of some kind. Speaking of enemies, we saw propped against the wall of the father’s hut, an assegai, the traditional spear used in battles with hostile tribes. Seemed anachronistic to me but who knew what was going through the old guy’s head. William’s father was also the village drum maker. Though reluctant to take any money for it, we purchased an old derelict drum (see below)from him, discarded behind one of the huts and now a prized artefact from our time in Africa.

Nathalie learning how to pound corn with Eva. I’m sure they all got a great kick out of her efforts. To watch the effortless, rhythmic and powerful motion of the local women and girls is impressive. The resulting cornmeal (polenta) is the basis of sadza, the traditional dish of Zimbabwe and, under different names, the staple food of much of black Africa. This wholesale adoption is all the more remarkable given corn was only introduced to Europe and Africa from the New World in the 16th century, along with tomatoes, potatoes, sweet potatoes, cassava and groundnuts. What did the New World get in exchange? Smallpox and assorted invasive species!

Two peas in a pod. Nina and William & Eva’s son Joseph were inseparable friends. One unforgettable day William forgot to close the front gate when I came home for lunch and these two decided to take off and explore the neighborhood on their tricycles. An absolutely frantic search ensued as they were nowhere to be seen, this in a country where witchdoctors (n’angas) are said to harvest the organs of young children as a source of powerful medicine (muhti). They were found, maybe a block away, oblivious to our parental concerns. Leaving the front gate open never happened again!

The iconic Balancing Rocks of Zimbabwe. Rocks stacked like these could be found in many parts of the country, which during the 3 1/2 years we lived there, we explored extensively.

Of course, the most significant outcome of our time in Zim was the birth of our son Nico. Once settled, with the stresses and strains of Angola behind us, Claire got pregnant (with some help from me!). Private health care in the country was reasonably good and despite a somewhat difficult pregnancy and a long, arduous delivery Nico was born healthy and hearty in Avenues Clinic, Harare in October, 1993

This was on the day when Claire came home from hospital after giving birth. William had made for the occasion these spectacular bouquets from flowers on our property. I think he missed his calling!

Nico ‘desecrating’ Cecil Rhodes’ grave! Rhodes, a high achiever by all accounts, was the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. His British South Africa Company founded Rhodesia which, with independence, became Zimbabwe and Zambia. He gained a near world wide monopoly on diamonds through his company De Beers and his estate funded, in perpetuity, the Rhodes Scholarship….among other notable achievements. Regardless, his autocratic ways and racist-colonialist views remain a blight on his legacy.

We came upon this random pile of primarily, elephant bones on one of our many camping safaris. Why they were there was a mystery. Was it the site of a major cull? Were they to be made into glue?….or possibly bone meal fertilizer? We never did find out.

One of the more fascinating aspects of Zimbabwean arts and culture is stone carving. A rich vein of serpentine and similar hard stones (the Great Dyke runs through the country) provide plentiful and inexpensive raw material. Encouragement through various unlikely agents in the latter half of the 20th century succeeded in developing this now internationally recognized art form. The photo above is from the village of Tengenenge where all of the 300 or so families make a living from carving stone. The village is a riot of countless carvings, scattered throughout the dispersed, humble rondavels (the typical round African hut) of the carvers. A unique and fascinating place to visit.

On the left, a favorite piece of ours carved in ‘mango’ serpentine. On the right, my first attempt at carving stone. In many ways, it was a product of my frustration with my work with CARE Canada. I bashed away at that rock for quite some time, using rudimentary hand tools made in country. I hired a young kid to do the final polishing.

Our lives were constrained and travel opportunities severely limited in our previous postings (Mozambique, Nicaragua & Angola) due to either civil war or similar, low level guerilla activity. Zimbabwe, on the other hand, was peaceful and stable allowing us to travel to all corners of the country. The spectacular rock dome in the background was a common sight and is indicative of the great rock climbing potential in Zim. I managed to get out for a little climbing during the visit of brother John and his wife, Carole but options and ‘beta’ (information) was scarce. Surprisingly, some online research indicates there has been very little growth in the sport since our departure almost 30 years ago. Given the worldwide growth in the sport, one has to wonder why this hasn’t occurred in Zimbabwe.

Another fascinating aspect of local art was the ancient cave paintings. There are literally thousands of these sites around the country. Though difficult to date they are typically thought to be 2,000 to 3,000 years old and some claim that certain paintings might be as old as 10,000 years. Despite their archeological significance and fine artistry they are not protected, have no explanatory signage and only rudimentary trails/information if one wants to visit them. In my untutored mind, they rival the world famous prehistoric, paintings of Lascaux, France .

My work with CARE Canada….I almost don’t want to talk about it. It’s brings up painful memories, so I’ll keep it short. I was initially responsible for getting the CARE Canada mission up and running. Zimbabwe was not the easiest country to work in, as the government insisted on being involved in everything, which of course should be the case, but it also complicated/delayed everything. Patience and diplomacy were essential, neither my strong suits, moreover the country had decent infrastructure, a relatively sophisticated economy and fully capable locals. The drought that had initially brought CARE to Zimbabwe was more or less over so whatever new programming needed to be well thought out, longer term, development initiatives (as opposed to emergency relief type programming) and developed in conjunction with either local NGOs or the Zim government. I got started on the above but without clear authority or guidance from CARE Canada. To complicate matters, CARE Britain and CARE Australia parachuted in program staff, neither particularly experienced nor wanting to work under any sort of direction from me. Eventually a temporary Country Director (CD) was brought in from CARE USA to ‘get things on track’ but in my estimation just complicated matters.

Meanwhile I was working on what I thought were appropriate, sustainable and very interesting project possibilities, that included: 1. Small scale dam rehabilitation on the Communal Lands to improve agricultural production, 2. Working with an existing government program that sought to compensate rural communities that lived adjacent to game parks and consequently suffered the impact of wild animals on their livestock and farms and 3. Expand the capacity of existing village Savings Clubs to provide peer to peer micro-lending (based on the Grameen Bank model). All of the above are relatively complex, long term development projects that demand a real commitment to your local partners and the project beneficiaries. Despite the glacial pace on progress, this work provided some much needed job satisfaction. Regardless, if it wasn’t for the many other positives in our lives I would probably have pulled the plug on CARE at this point.

My desire to hang in there was reinforced by the fact that Claire had landed a couple of good part time gigs, one with the US Peace Corps providing health services and orientation to incoming young American volunteers (i.e., potentially, sexually active young people as HIV/AIDs was exploding in Africa) and another with the International School, where she was setting up an in-house health care clinic. Along with mothering two kids under three and supporting her stressed out husband she had her hands full.

And then, it all come to a head! CARE Canada finally found a Canadian to assume responsibility for the mission. The new Country Director was a brash, fast talking, ‘food cowboy’ (i.e. experienced in food aid delivery in war or natural disaster type scenarios). Within weeks of landing in country he was firing off disaster relief, project proposals to funding agencies (CIDA, USAID, ODA, etc.) none of which, IMO, had any relevance to the situation in Zimbabwe. Shortly afterwards, the Desk Officer from Ottawa arrived to presumably offer me the Assistant Country Director position. As we sat down for an in-depth get-to-know-each-other interview, I mistakenly (naively, stupidly….I could go on!) spoke my mind on the ill-advised direction espoused by the incoming CD. The following day she reported to him everything I said. As a result, he wanted me out of there immediately. It was certainly not the way I wanted to end my ‘career’ with CARE but, in the end, it was for the best and eventually led to some very interesting and challenging work in a wholly new area of development assistance. Tales for the next installment.

Always interesting and well written, Jim. Thank you for this. Denise Sent from my iPad

LikeLike

Thanks Denise and Happy New Year to you and Pete.

PS – Ran in to Marion the other day (first time in many years) and had a nice chat.

LikeLike

hi there Claire / Jim, long time with your tales from “good old times”….not always good.

As we both often experienced in Mozambique, trying to do business or pushing construction-schedules and sometimes frustrated about lack of progress: A.W.A….. “Africa Wins Again”….. but your Zim-experiences showed that also “Assholes Win Again”…….

Well…not always…..and as we much later learned during after bushwalk in Kalahari (sitting near campfire 2 yrs ago talking about “development-aid”) from a bushman-guide, who told me “you have a watch, but we have the time”.

LikeLike

Hi guys

Love the words of wisdom from your African guide. Of course, things can be frustratingly slow but also change in Africa can be very fast. We’ve often considered returning – maybe doing a bike tour of Rwanda, where we have some connections. Then again, the recent events in the DRC most likely abetted by the Rwandan government might change those plans.

All the best

LikeLike

Ma très chère Claire et très cher Jim, vous avez vécu des expériences traumatisantes mêlées d’expériences plus intéressantes et valorisantes. Votre désir, si je me souviens bien était d’aider, d’informer et de développer leur milieu de vie. Vous aviez à coeur de leur apporter vos connaissances et en retour Care Canada n’a pas su vous aider; ils l’ont compliquer. Il faut dire aussi et peut-être suis-je dans le champ, que ces peuples ne parlaient pas votre language et ils ne savaient peut-être pas ce que vous veniez faire là. Vous deviez vous faire comprendre et expliquer le plus clairement possible votre souhait et désir de les aider. Ce qui déjà n’était pas si simple. Je suis sûr que vous leur avez apporté éveil et amélioration à bien des points de vue.

Nous avons encore les cassettes de nouvelles qu’ont s’échangeaient. Je ne me souviens pas de nos discours, toutefois, nous attendions de vos nouvelles à chaque fois. Et nos filles y étaient très attentives à notre lecture. Ça m’a fait drôle de voir Nathalie sur l’une des photos qui pilait du maïs; très attentive à ce qu’elle fait. Elle fut très heureuse d’être avec vous. Elle avait tellement dans l’idée de vous rejoindre et elle l’a fait. Vers l’âge de 10 ans qu’elle me disait qu’elle partirait.

Nous vous aimons, merci infiniment de tout ce vous nous partagez; c’est très instructif. Lise et Jacques

LikeLike

Merci ma très chère soeur. Ce fut toute une épisode de notre vie effectivement. Et la visite de Nathalie fut très agréable. En passant, les Zimbabwéen parlaient bien l’anglais. Notre trouble était du à la politique, comme si souvent et la corruption bien sûr. Ce fut quand même une bonne expérience!

LikeLike